The Obed Wild and Scenic River National Park (Obed) unit in eastern Tennessee is home to, among other things, world-class climbing. Injuries and incidents there range from lost or marooned paddlers to climbing injuries to falls from cliffsides of non climbers. With the access to both water and climbing activities, the NPS rangers created a program more than 10 years ago that gave an opportunity to all sixth graders in Morgan County, Tennessee, (where Obed is located) to spend a day in the Obed with rangers and volunteers climbing and paddling.

Students get to participate in top rope climbing with ropes set by staff. Helmets, harnesses and climbing shoes are provided, along with experienced belayers. The crag is accessed by a narrow rocky trail that climbs 100 feet in elevation over about a 600 yard distance. Any injury that necessitates carryout instead of walkout will take several hours or longer due to retrieving a litter and organizing volunteers for the task.

During a recent school program, a 12-year-old boy was participating with both of his parents present. Observing the young boy walking with assistance up the rock steps, it was obvious there was a long-standing neurological deficit. Speaking with parents, staff learned the boy had a neurodivergent disorder and also some type of lower limb muscular dystrophy. He expressed he wanted to attempt the climb so, with his parents’ permission, he was placed in a harness and helmet and attempted to climb a route where if he came off rock, he would be swinging in free space and not stuck on route. His attempt (with assistance) was short but he did make it up around eight feet of rock.

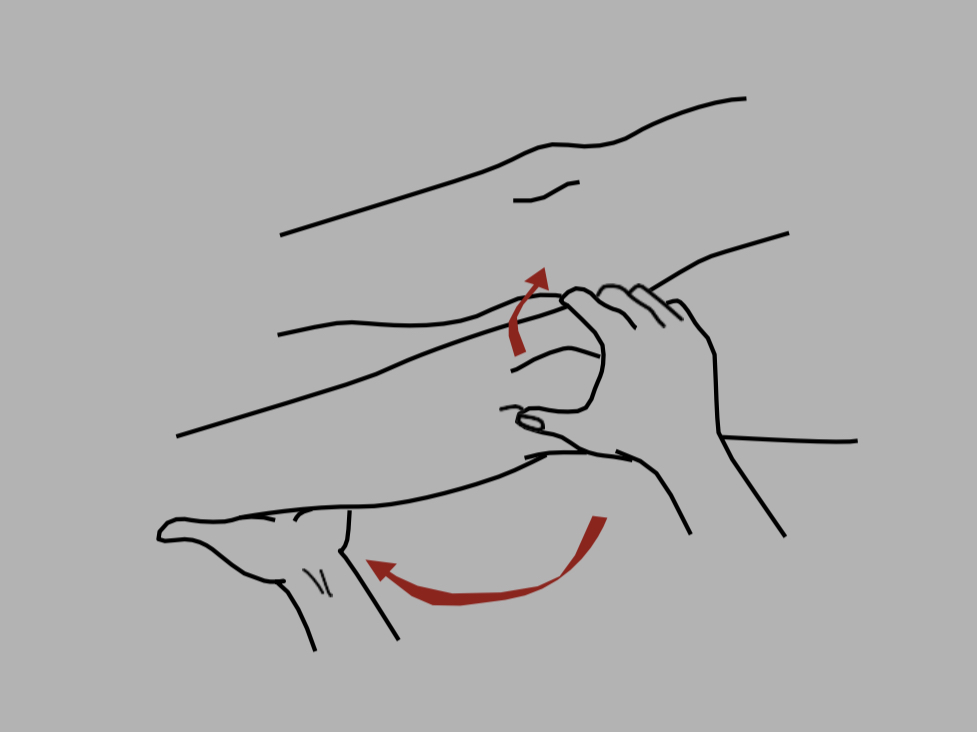

After taking him off rope, he walked away with his father assisting and proceeded up a set of rock steps. Part way up the steps, he suddenly went to the ground screaming with his father holding him. His mother immediately came to his side and was holding him from behind. His movements were rocking in motion and his parents expressed that he tends to shut down with extreme pain. Staff was to his side within a few seconds and found the boy lying with his right leg bent up at an estimated 120 degrees at the knee and in obvious pain. His parents relayed that his knee had dislocated several times before. A retired emergency medicine (EM) physician on staff at the park examined the boy’s knee and determined he suffered a lateral patellar dislocation. With the boy’s mom wrapping him from behind and dad holding his hips, the EM physician gently extended the leg while applying medial pressure on the knee cap. Once the leg was completely extended, the knee cap slid back into place and the young boy immediately stopped crying. Before allowing him to stand, a modified patellar brace was made out of athletic tape and a cushioned roll of Coban was applied over the patella.

Once dressings were in place, a discussion ensued about how to get the patient down to his parents’ car. The patient stood up with help and wanted to walk down. With assistance from parents and staff volunteers, he made the journey back to the car without further incident. The time from his injury to getting to the car was less than 30 minutes. His parents took the boy to his primary care provider where an x-ray was performed. No fractures were seen and follow up with physical therapy was initiated.

Dislocations of any kind in the backcountry can be difficult to manage. Any lower extremity injury can make extraction difficult if the patient cannot walk or assist in their own movement. Litter carryouts necessitate much more equipment, manpower and time. When possible, indicated and allowed by training and protocols, dislocation reductions can reduce pain significantly, minimize further injury, and make evacuation much easier. Patellar dislocations are not true knee dislocations but that may be how the layperson relays the information.

The discussion of whether to allow an EMR (or WEMR) to reduce dislocations or not is an appropriate discussion to have with your Medical Advisor/ Medical Director.

Protocols within the National Park Service EMS (DOI) have Nationally Expanded Scope that allows EMTs and above to reduce a Laterally dislocated patella. Our protocol is as follows:

Procedure 1210:

NOTE: ALL Reductions MUST have medical command (MC) approval prior to performing

REDUCTION OF DISLOCATED PATELLA

(KNEECAP)

(Only Laterally Dislocated Patella)

1. Assess other injuries, knee and distal circulation, sensation, and motor function.

2. Confirm indications (ALL must be present):

A. Greater than two hours transport time to hospital or clinic

B. History of indirect “lever-type” trauma to knee rather than direct blow

C. Obvious lateral displacement of kneecap to outside

D. Knee held flexed (bent) and patient with limited ability to straighten knee voluntarily

because of pain

E. No physical findings of direct knee trauma (e.g., knee lacerations/contusions/abrasions)

F. Procedure does not delay the care and transportation of life-threatening injuries.

3. If all indications are present, contact Medical Control for authorization to reduce.

4. Apply steady, gentle pressure from lateral (outside) to medial patella and simultaneously straighten leg.

5. If successful, knee should be immobilized in extension (straight).

6. If there are no other extremity injuries that prevent walking, patient may ambulate with immobilization (e.g., ensolite pad wrapped and secured around leg). Minimize walking unless necessary to facilitate evacuation and patient states there is no significant pain.

7. If unsuccessful, time/injuries do not permit reduction, or all indications have not been met, knee should be immobilized in the position it was found.

8. Reassess distal circulation, sensation, and motor function.

9. Document procedure.