There are missions and then there are missions. The former often get planned over late night beers, or early morning coffees. You and your friends toss out lines you want to ski, routes you want to climb, partners you can sandbag, and days you can take off work. The latter get planned…well…whenever they choose. Often in the middle of the night, before a workday, and in the middle of a storm cycle. Regardless of mission ‘type’ (recreational or rescue), advance planning occurs on a spectrum. For recreational missions, that spectrum can be wide, accommodating both those people who prioritize spontaneity and the unexpected, and those who don’t like surprises. Or fun. For SAR missions, risk tolerance is much lower which forces the spectrum to be narrower.

An important component of mission planning is assessing the environment, both for initial deployment and additional operational periods. Environmental conditions such as temperature, winds, and precipitation rates give clues about the potential for hypothermia, heat stroke, and dehydration for both rescuer and subject. Other conditions such as river stage, avalanche hazards, terrain slope, and recent fire perimeters can inform decisions about ingress and egress routes.

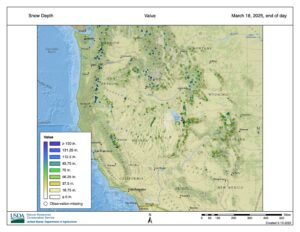

In the United States, SAR teams benefit from an impressive portfolio of freely available, publicly-financed streams of data which assist decision making and mission planning. For example, the National Weather Service uses a 2.5 km grid for its operational forecasting system and forecasts are issued two to four times per day. Additionally, the Natural Resources Conservation Service operates a network of over 800 snow telemetry (SNOTEL) stations in the western U.S. that provide hourly information on snow depth, snow water equivalent, and air temperature.

Map of the western United State showing the distribution of snow telemetry (SNOTEL) stations operated by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

When it comes to winter or spring missions, the United States Forest Service (USFS) contributes as well, through the partial funding of 13 avalanche centers. Simon Trautman is the director of the National Avalanche Center, which functions as an umbrella organization providing guidance, training and technical support to the other regional centers. These centers are all public-private partnerships, which Trautman cites as an asset, noting “you want that steadfast nature of a government agency coupled with the dynamic nimble nature of private business.” The avalanche centers synthesize and interpret many of the data streams mentioned above to create their foundational product which is the avalanche forecast.

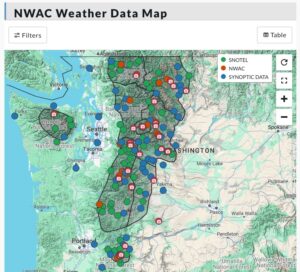

“To create an avalanche forecast you need good weather models; you need good mountain weather stations and telemetry; you need field observations for the area that you’re covering,” Trautman said. The support that USFS avalanche centers provide to SAR work has additional layers. Often, one of the centers will provide weather and avalanche ‘point forecasts’ in response to an activation. In some locations like Mount Washington, New Hampshire, and Mountain Shasta, Calif., USFS personnel are ‘boots on the ground’ as the primary SAR response team.

Regional weather stations that provide data to the website and mobile app of the Northwest Avalanche Center. (nwac.us)

Examples of SAR activities that have been substantially impacted by environmental data abound. Eric Rosenberg and Guy Mansfield are the president and vice-president of the Washington State SAR Planning Unit (WASSPU). WASSPU provides remote or on-scene planning assistance and resources for many agencies, including the MRA teams in Washington. Rosenberg notes that WASSPU participates in 15-20 missions per year and “we get called in once the mission starts getting a little harder, usually operational period (OP) 2 or the end of OP1.”

Mansfield points to the 2019 rescue on Liberty Ridge (Mt. Rainier) as a particularly good example of mission planning relying on accurate, timely weather information. In that incident, climbers issued a distress call on June 3. Rescue efforts on June 3rd and 4th were hampered by strong winds, which affected air assets. WASSPU arrived on site June 5th and worked closely with rangers to obtain and communicate numerous weather forecasts and products. These forecasts were instrumental in identifying a weather window on June 6th, which allowed for the extraction of the climbers by a National Park Service helicopter.

Sunrise over the Oregon Cascades as members of the Corvallis Mountain Rescue Unit work to help a stranded climber down Wolf Rock. Photo by Dan Sherman

A bit further south, Portland Mountain Rescue is one of five MRA teams in the state of Oregon. A resource of Clackamas County, PMR is known for their presence on the busy slopes of Mt. Hood. Paige Baugher is a Rescue Leader and the Public Information Officer for PMR and helped lead the Leuthold Couloir mission in 2022. Baugher notes that, following any activation, the Northwest Avalanche Center’s (NWAC) website is a key planning resource.

“They have meteorologists that work for them as well as avalanche forecasters, and all of them all get together and come up with this brilliant avalanche forecast, and also a meteorological forecast which is super useful.”

In the 2022 Leuthold Couloir mission, two climbers fell, with one sustaining fatal injuries. The weather deteriorated rapidly during OP1 and, after the successful extraction of the live climber, the mission was paused. The recovery of the deceased climber did not occur for several months, and Baugher notes that NWAC was an important resource in determining the timing, through phone calls, on-site evaluations of the slope, and other expertise.

Members of Corvallis Mountain Rescue Unit head to Leuthold Couloir on Mt. Hood to provide mutual aid to Portland Mountain Rescue. Winds were estimated at 50-60 mph for much of the mission. Photo credit: Tyler Deboodt.

It’s clear that SAR work is increasingly data driven. And it is also true that sometimes ‘more is less’ and too much data can lead to ‘analysis paralysis.’ However, a third truth is that reliable, real-time, and high-resolution information about the world around us greatly improves mission outcomes, in terms of rescuer and subject safety. Having grown accustomed to the rich and diverse sources of environmental data available to us, how would the SAR enterprise be affected if those data sources were degraded? What if there were fewer forecasts, or fewer weather and SNOTEL stations? What if these data products were taken out of the public sector and were privatized?

“All of our communities have learned how to make it work with the tools at hand. And if those tools at hand cease to exist our systems will break down,” the National Avalanche Center’s Trautman said. “Our systems are highly dependent upon one another, and we will not be able to produce the same avalanche forecast we do today if the SNOTEL system goes away tomorrow.”

A less-informed mission planning process will lead to increased uncertainty and risk for rescuers and subjects, and slower response times for SAR teams, according to Rosenberg and Mansfield of WASSPU. Baugher of PMR agrees, noting that “we would be sending our teams into areas that could be dangerous without knowing the full information.” Baugher also notes the potential impact on recreational users who, now and again, turn into SAR ‘customers,’ by observing “without NOAA and these other resources, I would really fear for public safety.”

The author catches some shuteye after climbing to the red saddle of Mt. Jefferson in search of a missing climber. A combination of hot sun over-baking the snowpack and poor weather forecasts for the next operational period led to pulling searchers out of the field. Photo credit: Tyler DeBoodt.

SAR team members are not computers and there is no magic algorithm for conducting a mission. Situational awareness is empirical and, to share a phrase I learned in a Professional Avalanche Search and Rescue (ProAvSAR) class, we should move through the mountains as artists as much as engineers. However, data is information, and information supports decision making. You might be a recreational climber wondering if you should head up into a whiteout on Rainier because your permit says today’s the day. Or you might be a mission coordinator looking to mitigate risk for your hasty team. The substantial investments by the federal government in monitoring and modeling environmental data are admirable and give us one of our most versatile tools as we work and play in our mountain environments. Let’s not take them for granted.

Dave Hill is a Professor at Oregon State University who studies snow distribution and evolution in mountain environments and how snowpack responds to changing climate drivers. He is an affiliate member of the American Avalanche Association, a National Geographic Explorer, a member of the Science Alliance of Protect our Winters and an MRA member through his membership in the Corvallis Mountain Rescue Unit in Oregon. He is also a volunteer Climbing Steward for the Mt. St. Helens Institute. Where you find snow, you’ll find Dave. Dave can be reached at: david.hill@cmru.org

Dave Hill is a Professor at Oregon State University who studies snow distribution and evolution in mountain environments and how snowpack responds to changing climate drivers. He is an affiliate member of the American Avalanche Association, a National Geographic Explorer, a member of the Science Alliance of Protect our Winters and an MRA member through his membership in the Corvallis Mountain Rescue Unit in Oregon. He is also a volunteer Climbing Steward for the Mt. St. Helens Institute. Where you find snow, you’ll find Dave. Dave can be reached at: david.hill@cmru.org