By Alexis Alloway, Winter Training Coordinator, Everett Mountain Rescue

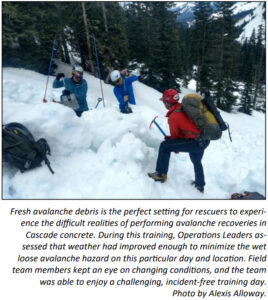

This article first appeared in its original form in The Avalanche Review, 37.2, December 2018 It’s 9:40 p.m. on a stormy winter evening. Twenty-eight inches of new snow, with around 1.5 inches of Snow Water Equivalent (SWE), has fallen in the last 24 hours, winds have been steadily blowing, and weather conditions are showing no sign of improvement. The avalanche danger is “High,” and a thin layer of facets lurks atop a crust several feet below the snow surface. You’re about to turn in for the night when you receive a text message announcing that two teenage boys are overdue after departing earlier that day for an afternoon ski tour. The general area where they were last seen consists of challenging to complex avalanche terrain. As an Operations Leader in your local Mountain Rescue Unit, how do you respond? This scenario was a real avalanche accident that happened near Snoqualmie Pass in Washington’s Cascade Mountains in February of 2018, and these dangerous conditions are somewhat typical of the handful of winter missions that nearby Mountain Rescue teams field each year. Common themes include terrible weather; considerable or high avalanche danger; darkness or impending darkness; challenging to complex terrain; poor visibility; and lots of uncertainty. Most of our winter missions are searches, which further increases risk to rescuers by requiring them to travel through more terrain than if they were responding to a known location, thus increasing their exposure. Besides the objective hazards, another risk management challenge is that most Search and Rescue teams consist of volunteer rescuers, many of whom have little or no professional risk management or professional avalanche work experience. These members don’t get paid to attend trainings, they don’t have a supervisor, and they don’t receive coaching, feedback, or other professional development related to terrain selection, stability assessment, and group management. Most rescuers have learned about avalanches in the wicked learning environment of the backcountry, meaning they do not have adequate experience in an instant-feedback environment to develop true avalanche expertise. Even those rescuers who frequent the backcountry may be unconsciously incompetent when it comes to managing risk, perhaps having gotten lucky over the years instead of making good decisions. As if the objective hazards and lack of expertise aren’t enough, human factors run rampant during a SAR. When someone is missing or injured in a winter environment, real people’s lives are on the line, and the pressure to act and get results can feel enormous. Common hu man factors include expert halos, rushing, people being afraid to speak up, and what can only be described as good, old-fashioned “testosterone poisoning” (overconfidence in one’s abilities and underestimating hazards). If we look at accident potential as the realm where objective and subjective hazards collide, it’s pretty clear that avalanche rescue is a risky business, especially when undertaken by volunteers. In Everett Mountain Rescue, we recognize that avalanche response is the skillset where our volunteers are least equipped to identify and manage risks. Of our membership of 70 people, only about a third recreate in avalanche terrain in the winter, and most of them only a handful of times per year. The average team member has a recreational Level One training, and while a few of our members volunteer to assist with teaching Level One avalanche classes, almost none are paid avalanche professionals. Our team does not get many winter SAR missions due to the fact that most alpine terrain in our jurisdiction is inaccessible all winter. Our nearby Mountain Rescue teams seem to have a similar demographic. For us, avalanche responses are a “low probability, high consequence” event, meaning we have few similar historic events to learn from, yet there is a lot at stake. After fielding several winter missions where members raised concerns about risk management, we started to really see our team’s vulnerabilities. The resounding advice from the professional avalanche world seemed to be “get a system,” so we decided to give that advice a try. After reviewing a couple of existing checklists, we felt they were not detailed enough to work well for our users, so we decided to create our own. During the winter of 2017-18, a small group of our volunteers developed and piloted an Avalanche Hazard Assessment (AHA) sys tem designed specifically for our Mountain Rescue unit. For the rest of this article, we will explore the components of this system, its bene fits and limitations, and tips for implementing an “AHA moment” into your own organization’s culture. HOW IT WORKS Upon receiving a request for SAR resources, our In-Town Commander (ITC) pages out the known information to a group of Operations Leaders (OLs) using the GroupMe app (an instant messaging system). Upon receipt, two OL-level individuals respond to the group that they will perform the AHA. Using a standardized AHA worksheet (see below), each of those individuals independently spend 15 minutes gathering information about snowpack, weather and terrain. Once the raw data is gathered, each OL analyzes the information and decides whether to deploy field teams or wait for better conditions. If they do opt to deploy, they create a run list for field teams, with an emphasis on identifying terrain that needs to be closed. A run list is a common risk management tool used in ski guiding, where guides meet in the morning and pre-determine which specific ski runs are open, closed, or on standby (needs further assessment) for the day. Once each of the two OLs has completed the AHA, they call each other on the phone and collaborate to create a finalized AHA that includes a run list and notes to field teams. OLs have the authority to order terrain for closure, and OL-level terrain closures cannot be re versed by rescuers in the field. Field teams can choose to close additional terrain based on what they find, but OL-level terrain closures are a final say. If the OLs can’t agree on a run list, they are encouraged to yield to the more conservative judgment call. Our local avalanche center, the Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC), has agreed to have their staff review our completed AHA forms during missions and give their input about our terrain choices. They also are able to provide us with point-specific weather and avalanche forecasts for locations further away from the ski areas, where data is more scarce. The completed AHA worksheet, along with supporting documents like slope-angle shading maps, Google Earth images, and terrain photos, is then paged out to all rescuers with the mission announcement. If we are not able to get OLs working on the AHA immediately, we have agreed it’s okay to start mobilizing resources toward the trailhead, but the AHA must be completed and communicated to Command before teams are actually deployed in the field. Our AHA also includes a standardized briefing sheet for all teams to complete before heading into the field, allowing them to make additional assessments at the trailhead. Just because OLs have not closed terrain doesn’t mean that terrain is necessarily safe, and we want to allow individual rescuers to maintain their veto power and create their own terrain closures if they don’t feel comfortable going into certain terrain. ADVANTAGES OF THIS SYSTEM Human factors are why smart people can do stupid things. The AHA is an attempt to minimize human factors in our decision-making by using a checklist and assessing obvious hazards from a level-headed perspective. By having our more experienced team members assess risk, and by using a collaborative approach rather than relying upon the judgment of one individual, we are harnessing the collective brain power of our team and providing some checks and balances against strong opinions from one person. If you are familiar with the Swiss cheese model of accident causation, we are adding another layer of risk management to protect individuals from harm. Another benefit of the AHA is that it slows us down and allows us to engage our logical, proactive brains instead of just our intuitive, reactive brains. This slowing down is minimal in the grand scheme of things, but it’s enough time that it does allow for critical and thoughtful analysis of complex variables. The systematic approach of working through a pre-set worksheet ensures we don’t skip steps that can easily be forgotten in the adrenaline-fused excitement of mission planning. Having the OLs complete the AHA ultimately saves the team time, as individual rescuers don’t have to spend mission prep time checking the avalanche forecast and pulling data themselves. To maximize effectiveness, our AHA was intentionally designed to be flexible and to avoid rule-based decision-making, which can prevent the use of situationally appropriate judgment. There is no mandate within our AHA that states that if data points meet a certain threshold, we can’t send teams in the field or we need to close terrain. It’s up to the OLs making the assessment to determine whether conditions warrant terrain closure or delaying or declining the mission from the start, or whether field teams can make that assessment on their own.

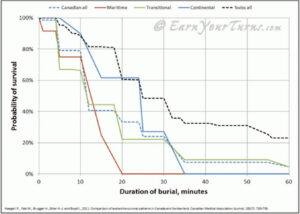

We recognize that sometimes you can’t truly assess conditions until you are in the field, and we encourage OLs to only close terrain preemptively if they feel certain that there is an imminent threat to rescuers. Finally, maybe the best part of the AHA system is that it has proven to be an excellent training and communication tool that is improving the overall avy-savvy of our team. By using the AHA even for routine trainings, we are role-modeling what a thoughtful hazard assessment looks like. The more people practice using it, the better they get at analyzing and communicating about avalanche risk. We even had one of our rescuers use the AHA worksheet to help her teenage son analyze his intended snowshoe trip during high-avalanche danger, and make the decision to postpone the trip for another day. Our mission of saving lives through rescue and mountain safety education? Accomplished. DISADVANTAGES OF THIS SYSTEM The AHA process does take time, and we all know that time matters in avalanche rescue . . . but does it? In companion rescue, yes. Organized rescue is another story, though. The greatest myth perpetuated among SAR volunteers is a misguided belief that time is of the essence and that they must hurry to deploy teams in the field. The reality is that, at least in our region, by the time rescuers from Seattle or Everett make it to the mountains (a minimum one-hour drive), anyone who has been fully buried by an avalanche will be dead (see graph of survival times in maritime climate). Our SAR teams either perform body recoveries of people fully buried, or we assist people who can

wait the extra 15 minutes it takes to perform an AHA (read: they are not having an airway emergency). With rescuer safety as a priority over subject safety, there is ALWAYS time to assess conditions before heading into the field, even for SAR teams within closer proximity to the mountains. To borrow from the Special Forces, remember that slow is smooth, and smooth is fast. Even though time doesn’t matter as much as in a companion rescue, we still want to perform our AHA efficiently and get teams in the field. The first time we piloted the AHA, it took nearly 30 minutes for the testers to complete the worksheet. The biggest challenge was not gathering the information, but getting that information into the electronic worksheet format. Through piloting and revamping the work sheet, we designed a more efficient and user-friendly system. Like any system, the AHA works best with training, and we have seen that trained users can complete it in about 15 minutes. That brings us to another disadvantage of the AHA system: user skill set and backcountry experience. Our AHA is designed for expert back country users who are proficient with gathering online data and analyzing terrain using topo maps, satellite images, and their own person al terrain knowledge and experience. Inexperienced users will struggle to find this information in a timely manner, and they may struggle to visualize what terrain on a topo map actually looks like in real life. Additionally, inexperienced users tend to overestimate risk and they struggle to use judgment and make decisions in the face of complexity and uncertainty. Because our AHA is being performed indoors, before our teams are in the field making their own snow and avalanche observations, the AHA output is only as good as the data input into it. While we are lucky to have pretty good information available online for western Washington, we still have all seen times when conditions in the field don’t align with conditions report ed online, or where we can’t find information that we need or want. AHA users need to be able to make judgment calls, such as recognizing when weather data seem a little off, or recognizing when they need to skip a data field if the information isn’t available. They also need to have the common sense to communicate areas of uncertainty in their assessment so those are as can be addressed.

NOW WHAT?

For Everett Mountain Rescue, the AHA system is still new, and we have only gotten to deploy it on a small amount of missions and trainings. Despite its newness, the preliminary results of using this system have been incredibly positive. By using the AHA during routine winter trainings, we have provoked excel lent discussions about avalanche risk, with high engagement from participants. People are showing up to trainings and missions better prepared than ever with knowledge about weather, terrain and snowpack. Using the AHA has sparked a renewed interest in avalanche safety and education within our members, and our unit leadership paid for 30 of our members to take avalanche trainings in January of 2019. Finally, other regional Mountain Rescue units have been asking to see our AHA system, which shows that there is a regional interest in improving risk management during winter SAR missions.

For our team, the biggest challenge of using an AHA system was navigating our team through the process of change. While the majority of our team members openly welcomed the new system, there was a small but vocal minority that op posed it. We encouraged these people to give their input on how to improve the system, and soliciting this input helped gain buy-in. If you are involved with a Mountain Rescue group, I encourage you to up your team’s risk management game this winter by adopting a systems approach to avalanche safety. Feel free to use our system as a template, or create your own. Regardless of what you do, something is better than nothing, and even a small, simple checklist can go a long way in improving your team’s performance. And finally, if you are going to adopt a systems approach, a few words of advice: Have a plan. Many people struggle to embrace change, and you will need to create a change-management plan in order to set yourself up for success. Identify progressive, like-minded people within your team, and recruit those early adopters to the cause. Get the support of people in key leadership positions. Once your leadership agrees on the need for change, start planting the seed in unit members that change will be coming, and explain why. Get group input in developing and piloting your system, and have respected team members voice their support and role-model using it. Be realistic and frame your AHA as a work in progress that will require troubleshooting and modifications. Start using your AHA during trainings and missions, and be sure to consistently use it for every winter field event. Before you know it, people will come to expect it and appreciate it, and you will have made a substantial improvement in your team’s professionalism and culture of risk management. Winter 2018 9