The subject was a 60-year-old female hiking down from the summit of Pikes Peak (14,109 ft) on a sunny, September day. She stepped on a rock and twisted her left ankle, resulting in lateral (outside) left ankle pain only and no other injuries. El Paso SAR (Colorado Springs) and Douglas County SAR (South of Denver) responded to the subject at 13,500 ft.

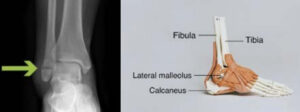

The physical exam was significant for tenderness over the lateral malleolus (fibula, as pictured below) and the lateral ankle ligaments. She did not have tenderness over the medial malleolus (inside, tibia) and had no deformities. Circulatory, sensory and motor (CSM) function was intact.

Field Management

SAR applied a SAM splint by cutting the splint in half, placing one side on each side of the ankle, wrapping top with ace wrap, and taping one figure 8 around the shoe as demonstrated in the images below. This technique allows for more support and maintains shoe traction.

Rescue Decision Making

SAR took into account the following several points prior to allowing her to hike out on a potential ankle fracture:

1. The subject had on low-cut trail running shoes.

a. It is also easier to identify a deformity with this type of footwear, but if in the field consider the subject’s footwear (motorcycle, ski, snowboard or other type of large stiff boot).

b. Her shoes allowed for a detailed exam to be performed without removal, including points of tenderness and CSM.

c/ High-top boots don’t allow for a detailed exam but do provide more stability.

d. Whether to remove the boot or shoe is a long topic but briefly, the boot/shoe itself provides insulation and support and once you take it off, it will be difficult to impossible to put back on.

2. SAR was less concerned about lateral ankle pain because the fibula, that is located laterally, is not a weight-bearing bone.

a. The tibia, however, is weight bearing and located medially, so localized pain on the medial (inside) aspect of the ankle may not be appropriate for hiking.

3. Evacuation was not easy but was attainable with a van waiting at the summit.

a. The terrain was a mountainous trail but there was a vehicle at the top for transport.

b. If this was a longer evacuation or terrain was more challenging, then having the subject walk may not have been feasible.

4. Having the correct supplies and a subject with a good attitude makes all the difference. The subject was able to walk 5 steps with a well-placed splint, poles and motivation.

5. Weather was good.

a. Extreme weather and unstable footing will complicate evacuation plans.

b. With deep snow, ice or more uneven terrain, a walk out would not be possible.

Discussion

Ankle injuries are the most common wilderness injuries that SAR encounters. While ankle injuries do not require a diagnosis in the field, simple principles can be used to make a decision about whether the subject can hike out on their own – which is safer for both the subject and the rescuer. Location of pain, degree of tenderness, an obvious deformity, subject reliability, and ability of the subject to stably bear weight and ambulate are factors when making a decision in the field. Generally a good exam and shared decision making between the subject and team with frequent re-evaluations are keys to a successful rescue.

While no specific clinical decision making tools exist to judge the risk of hiking out on an ankle injury, the Ottawa Ankle Rules (OARs) provide a 5-component evaluative tool that assesses likelihood of severity or complication of an ankle injury and can potentially be used as a guide to making this judgment call in the field. These components include bony tenderness along the posterior aspects of the malleoli, the base of the 5th metatarsal, navicular bone, and inability to bear weight both immediately after injury and for 4 steps during initial evaluation, with 2 or more positive findings correlating to increased likelihood of fracture that will be significant enough to be detectable on X-ray.

The OARs were designed to determine the need for X-ray in acute ankle injuries in order to screen out unnecessary imaging e.g. if sprained and not fractured, an X-ray will not provide useful information. They have been well validated with a high degree of reliability and accuracy in detecting specific types of fractures. They do not exclude all ankle fractures or significant ligamentous injuries but the argument can be made that if the exam is reassuring without positive findings using the OAR components then it may be reasonable for the subject to ambulate on their injury. They do not preclude the risk of worsened injury with ambulation. Regardless, the decision should be made using clinical judgment and experience of the rescuers and or their medical leadership.

Will Petitt is a Physician Assistant at a level one trauma center in Denver, working in Orthopedics for the last 20 years. He is also medical chair for Douglas County Search and Rescue. He is a regular, longstanding member of the MRA MedCOM, a committee of medical professionals that writes a quarterly contribution to the Meridian. For questions about anything related to medical issues, contact medcom@mra.org. Thank you.