Cassie Lowry, DO FAWM

MRA MedCOM

Climbing, in its many forms, has grown in popularity across the country at an estimated 67% increase since 1998. As outdoor sports continued to grow in popularity during the COVID pandemic, the frequency of injuries is likely to have increased as well. Many of the largest data sets predate the pandemic, but smaller studies recently released have consistently demonstrated similar conclusions.

Within the sport of climbing itself we can see trends in the injuries that lead to hospitalization of the athletes and pose the greatest safety challenges to these athletes and likewise the rescuers called to tend to them in the field. These insights provide tangible benefit for preventative education to the athletes, their advisors, and the climbing and rescue community. In a larger effort, it also provides the bases for the rescue community to serve wilderness recreationalists by continuing to support that education.

Familiarity with trends and unique injuries related to the sport may also provide specific insight to rescuers while caring for these patients and teams in high yield parts of the country in preparing for the warmer months when these numbers generally uptrend.

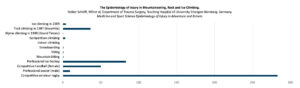

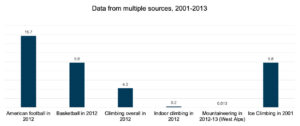

The data on climbing gathered from a massive study published in 2012 suggests that to does pose less injury-per-1000-hour risk than other popular sports such as basketball, rugby, or skiing, however retrospective data on sport-specific injuries and fatalities are not reported in a standardized manner so monitoring injury patterns and risk remains challenging, especially regarding recommendations for preventative measures. But in general, climbing can be considered less dangerous in this sense than other sports as it may be not as “extreme” as it’s been regarded in the past, especially with advances in equipment and technique over the past few decades.

[Click to view larger images of graphs and tables.]

Different forms of climbing also demonstrate different trends in rates, severity, and fatality of injuries within the sport as a whole. Mountaineering athletes, for instance, demonstrate higher rates of head and spine injuries as well as higher grade traumas and poly-traumas, while sport and alpine climbing see a high incidence of lower limb injuries, primarily fractures, sprains, and strains. Not surprising, alpine climbing sees greater risk than sport or “crag” climbing due to a larger number of objective hazards encountered in the sport similar to mountaineering but overall less risk in a general sense than mountaineering. A large 30 year retrospective analysis published in 2020 by the American Alpine Club also demonstrated the highest injury rates and severity in alpine and ice climbing.

The Risks in Climbing

The AAC data from the 2020 report also found a significant one third of reported injuries (865 out of the 2,724 climbing incidents) occurred during descent. Fatal accidents were most associated with rappel errors and unroped climbing, and like other studies discussed below there was consistently a strong correlation between lack of helmet use and severity of injury. A 1988 study from Yosemite also showed that experienced climbers were most likely to be significantly injured, however with the volume influx of new climbers this trend may or might already be shifting.

Although less than 12% of climbers evaluated in emergency departments in one data set reviewed were hospitalized for their injuries, most of them were due injuries related to falls. Notably, climbers were ten times more likely to be admitted for injuries obtained from falls from greater than twenty feet (which included both “whippers” and “decking”), illustrating a significant and tangible risk of serious injury related to this kind of exposure which is a common in lead climbing and unroped climbing including bouldering, free climbing, and free soloing.

The principal risk with falling is the impact on the descent or rapid halt of that motion. Not all falls can be completely mitigated by nature of the environment, however technique is consistently emphasized in the sport to reduce the probability of a greater distance during a fall and to avoid complications relating to gear. Most authors of the studies reviewed agreed that increased helmet use would arguably decrease the severity of injuries obtained by climbers and mountaineers, but the greatest risk across all forms of climbing is a significant fall.

The risk and consequence of head injury and blunt trauma are greatly increased by falling inverted. Helmets are not 100% protective but may reduce the severity of head injury, depending on impact forces.

Injury Patterns

Over-exertion or stress injuries may be avoided with proper technique, warm-ups, and stretching. Stress injuries unique to climbing include torn pulley tendons in the fingers, hamate fractures in the hands, and proximal hamstring strains which infrequently require evacuation but fractures and injuries related to falls were very common in the data sets examining climber injuries that were evaluated in emergency departments.

The most common injuries over all to require emergency evaluation have been fractures, strains, and sprains, and the vast majority of injuries sustained in climbing do end up in hospitalization. Injuries from landing on or impalement by gear are less common but the consequence can range from minor tissue damage to devastating neurological damage or paralysis. Reaching for carabiners or the rope during a fall increases the risk of rope burns, impalement, unclipping, and getting appendages caught in the rope as it coils and uncoils which can result in degloving and amputations.

In general, education in the climbing community may be the principal step to reducing the number and severity of preventable injuries that rescuers are called to every year. Mountain rescuers are in a unique position to often have experience that is highly applicable to all types of climbers. Engagement in the climbing community by rescue teams to continue to provide much needed mentorship and support for the ever-growing population of climbers and mountaineers.

Cassie Lowry, DO FAWM (Everett Mountain Rescue) is originally from Washington State, soon relocated to San Diego from Montana. She is a longstanding member of the MRA MedCOM, a committee of medical professionals that writes a quarterly contribution to the Meridian. For questions about anything related to medical issues contact us at medcom@mra.org. Thank you.